Tengbeh Town: its road-railside reality.

Where we live, 19a Old Railway Line, places us not just on what was until the early 1960s a narrow gauge rail line that climbed to the summit of the hills above Freetown, but also on the edge of Tengbeh Town. It sounds as if it should be a slumbering middle-England football club but in fact is a very vibrant community that clings to the precipitous incline on the side of a mountain and hugs the road which has a more manageable gradient.

Janice and I regularly walk down the hill for 10 minutes to where taxis have their terminus in the centre of the community. “Taxis” operate like a bus service which has no fixed route and the driver negotiates how many people he can cram in and how much each passenger can be coerced to pay. When I state our destination, the response of the young driver is not about whether he intends to go in that direction but is instead, “oh mohs yugimme?” And as in all trade negotiations, nothing has a fixed price in Freetown, there is “white price”.

In reaching the terminus we pass the high walled premises said to belong to the Minister of Finance, the headquarters of World Food Programme, a mosque of a very fragile construction, the sign boards to two independent churches, the Lutheran Bible Translator’s Offices, three schools for varying ages. Amongst all these is a myriad of commercial enterprises from football cinemas, car repairs, tailoring and clothing repairs, bread makers and sellers, fruit stalls and invariably they are all within or attached to a family home or the grounds of the home. So that the events of cooking , washing laundry and personal ablutions, are all within view of those who pass by. Be it day or night, there is constant stream of activity for which the idea of lunch time or afternoon/evening closing time would be totally alien to the rhythm of day by day survival.

Just how compelling and demanding life is on the margins of the road-railway line, was made even more graphic on a recent visit to the Conteh family, to see their home, to eat a little food and experience his mini enterprise which included the chance to view some premiership football in the ‘cinema’ he owns. Sam Conteh, a native Sierra Leonean, gives a clear account of how hard he has found it to legally defend the boundaries of the plot of land he inherited from his Krio stepfather. And Kortor his wife, is equally graphic about the physical confrontations that have occurred with intruders, land grabbers and corrupt police officers who appear on the pretence of having the power to evict. The Conteh’s home is a few metres from the old railway line, a humble timber framed structure that was constructed within a four day-night period, in order to assert their rightful claim and ensure their continuity as owners.

Their land is also adjacent to a thoroughfare, which clearly determined the positioning of a corrugated zinc sheeted shed which can seat 200 people in front of two TV sets positioned less than a metre apart and the sole reason for young men paying 8p each, to see two English Premier football matches simultaneously, with the commentary being switched from one to the other at half time. The sound system, a loud hailer, is located outside to advertise the location and broadcast the events being shown via a satellite dish, attached to the roof of a lean-to kitchen. In this microcosm of urban living, where a tenant of the Conteh’s, a middle aged woman who suffered a stroke eight months ago lives in two small rooms with her six daughters and various children , where a welding workshop functions with the aid of near deafening diesel generator and the lounge of the family home serves as retail outlet for cold water, major questions are raised about how the social context shapes the understanding of personhood, of being an individual and being human. In this the communal concept of being African – a person is a person because of people, is instrumental in appreciating how the community of Tengbeh Town functions.

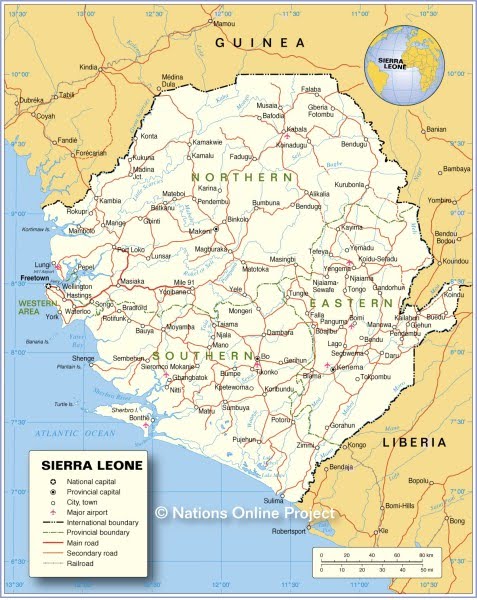

Our limited travel across Freetown confirms the widespread urban poverty which is reported as being ‘multi-faceted, infectious and compounded by high levels of inward migration and produces poor sanitation, uncollected garbage, an erratic water supply and intermittent power cuts’. As two new arrivals to a city, which may have close on two million people, we are part of the problem. It is therefore imperative that Janice and I, two Europeans, take seriously all that we encounter, whether they be individuals, communities, churches or educational institutions, and all of them African. In doing so, what and how we discover where we live and who we live alongside, is shaped by the events of recent history and that walk is both longer and more painful than the stroll we take down the old railway line.

No comments:

Post a Comment