Since my first extended stay in Southern Africa for a year before starting university, there have been several return trips to the West of the continent, both to gain experience with charitable organisations and for holidays. Whether fascination, curiosity or the refreshing change that comes with being in an environment that hustles and bustles to meet the necessities of daily life, there must be something which draws me to the continent. Five years through a medical degree, I have just returned from spending two months at Nixon Memorial Hospital, in Segbwema, a small town in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone. At the end of my stay, I joined what appears to be an ever growing list of fortunate people, who have experienced Peter and Janice’s hospitality in Freetown. I hope I can add some reflections and comparisons of health in a very rural region of the country to their blog.

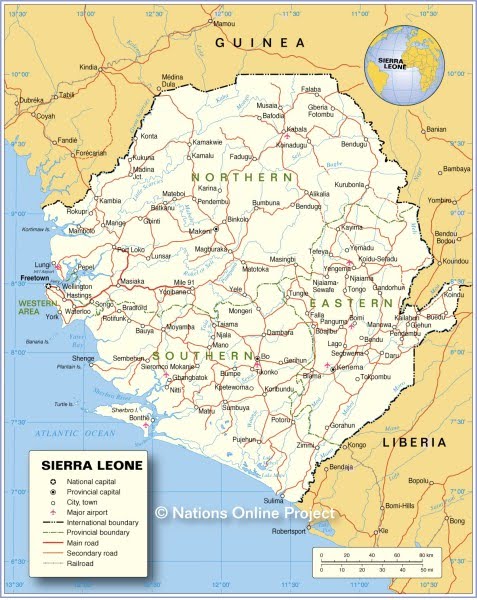

Since my first extended stay in Southern Africa for a year before starting university, there have been several return trips to the West of the continent, both to gain experience with charitable organisations and for holidays. Whether fascination, curiosity or the refreshing change that comes with being in an environment that hustles and bustles to meet the necessities of daily life, there must be something which draws me to the continent. Five years through a medical degree, I have just returned from spending two months at Nixon Memorial Hospital, in Segbwema, a small town in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone. At the end of my stay, I joined what appears to be an ever growing list of fortunate people, who have experienced Peter and Janice’s hospitality in Freetown. I hope I can add some reflections and comparisons of health in a very rural region of the country to their blog.There is a place about a mile outside Segbwema simply referred to as ‘the rock’, where I would sometimes walk to on a Sunday afternoon. A scramble up a weathered track, past the derelict remains of houses that used to accommodate

visiting doctors, rewards you with fantastic views across the tropical greenness that surrounds the village, with single storey dwellings and the new school scattered on the land in front of you. From the top of the rock, Segbwema is beautiful, serene and uncomplicated. This impression would be in stark contrast to how you felt on a Monday evening after a long day of clinics and ward rounds, where the complexity of the place revealed itself, both in the detail of malnourished children and women who suffered unnecessarily with complications associated with child birth, but also in glimpses of the compassion and often unanticipated humour that compose human nature.

visiting doctors, rewards you with fantastic views across the tropical greenness that surrounds the village, with single storey dwellings and the new school scattered on the land in front of you. From the top of the rock, Segbwema is beautiful, serene and uncomplicated. This impression would be in stark contrast to how you felt on a Monday evening after a long day of clinics and ward rounds, where the complexity of the place revealed itself, both in the detail of malnourished children and women who suffered unnecessarily with complications associated with child birth, but also in glimpses of the compassion and often unanticipated humour that compose human nature.Anyone who enters a role in the healthcare profession does so with the knowledge that, although many of the patients who they treat and care for will recover, there are some who will unfortunately not. The principle is consistent whether in Segbwema or London; what changes is the proportion of patients who recover or die and the frequency at which this occurs. The child mortality rate in Sierra Leone is among the worst in the world, with approximately one child in every five dying before their fifth birthday. During an earlier 5 week paediatric placement in west Wales, thankfully for the parents and children who visited the hospital, I had no exposure to children dying. On the third day of being in Segbwema, I was asked to confirm the death of a toddler. I had seen the child with the doctor thirty minutes earlier. She was malnourished with sparse, brittle hair and had a severe pneumonia. Antibiotics had been started, although there

had not been sufficient time for them to have an effect. Walking across the busy ward to the child, I was facing both an emotional challenge and a practical task I had not had to confront before. I placed my stethoscope on her chest and heard nothing. No heart beating, no breath sounds. No reflexes or response to stimulation. Student nurses quickly wrapped the body. The mother came, stood by the child, sighed, and walked away. Then life continued in exactly the same manner as it had the thirty seconds previously. The routine, normality and acceptance of the situation was perhaps the most upsetting aspect. Child and neonatal death is, unfortunately, entrenched and ingrained within daily life in Sierra Leone. Whilst assisting at the antenatal clinic and recording the number and outcomes of a patient’s previous pregnancies, it was not an uncommon situation for the woman in front of me to be pregnant for the fifth or sixth time, with four or five live births and only one or two children alive. Inspired by my short placements on the labour ward and birthing units in the UK, I was keen to increase my experience of obstetric care. Unfortunately, I only observed two births, both of which were still births, one a normal delivery, the other at caesarean. However, another student who was also at the hospital was involved in births where there was a very positive outcome for both mother and child.

had not been sufficient time for them to have an effect. Walking across the busy ward to the child, I was facing both an emotional challenge and a practical task I had not had to confront before. I placed my stethoscope on her chest and heard nothing. No heart beating, no breath sounds. No reflexes or response to stimulation. Student nurses quickly wrapped the body. The mother came, stood by the child, sighed, and walked away. Then life continued in exactly the same manner as it had the thirty seconds previously. The routine, normality and acceptance of the situation was perhaps the most upsetting aspect. Child and neonatal death is, unfortunately, entrenched and ingrained within daily life in Sierra Leone. Whilst assisting at the antenatal clinic and recording the number and outcomes of a patient’s previous pregnancies, it was not an uncommon situation for the woman in front of me to be pregnant for the fifth or sixth time, with four or five live births and only one or two children alive. Inspired by my short placements on the labour ward and birthing units in the UK, I was keen to increase my experience of obstetric care. Unfortunately, I only observed two births, both of which were still births, one a normal delivery, the other at caesarean. However, another student who was also at the hospital was involved in births where there was a very positive outcome for both mother and child.I fear that I am presenting too gloomy a picture of hospital life. It is often difficult to know what to express when trying to give an account of your experiences; attempting to get the balance right between describing the realities of the situation

without giving the impression of hopelessness would not be true. There were moments of happiness too, both in hospital and village life. One young boy was admitted with a muddled and incomplete story about falling from a tree. He had significant abdominal pain and initially it was suspected he may have ruptured his liver or spleen, associated with a very questionable prognosis. However, a conservative approach was taken and in addition to other medication, he was given a trial of treatment for typhoid fever, which can also present with abdominal pain. There was considerable collective relief when on the fifth day he had recovered and was standing smiling next to his bed. Hope and happiness also came in the form of discharging children from hospital and seeing how malaria treatment and blood transfusion could transform pale, listless, almost lifeless small bodies into active healthy beings ready to continue being children.

without giving the impression of hopelessness would not be true. There were moments of happiness too, both in hospital and village life. One young boy was admitted with a muddled and incomplete story about falling from a tree. He had significant abdominal pain and initially it was suspected he may have ruptured his liver or spleen, associated with a very questionable prognosis. However, a conservative approach was taken and in addition to other medication, he was given a trial of treatment for typhoid fever, which can also present with abdominal pain. There was considerable collective relief when on the fifth day he had recovered and was standing smiling next to his bed. Hope and happiness also came in the form of discharging children from hospital and seeing how malaria treatment and blood transfusion could transform pale, listless, almost lifeless small bodies into active healthy beings ready to continue being children. The approach to medical diagnosis in the UK can often focus on the minute detail; a raised marker on a blood test or even down to the smallest genetic mistake in human DNA. In Segbwema, without X-rays, blood tests other than a malaria parasite check, running water or electricity for the majority of the time, medicine is practiced with the broadest of brush strokes. Fever is treated as malaria, diarrhoea often as a worm infestation and a cough as a pneumonia or tuberculosis. Temperature is assessed with the palm of a hand on the patient’s forehead and anaemia is checked for solely by looking at the colour of the patient’s hands or conjunctiva of the eyes.

The approach to medical diagnosis in the UK can often focus on the minute detail; a raised marker on a blood test or even down to the smallest genetic mistake in human DNA. In Segbwema, without X-rays, blood tests other than a malaria parasite check, running water or electricity for the majority of the time, medicine is practiced with the broadest of brush strokes. Fever is treated as malaria, diarrhoea often as a worm infestation and a cough as a pneumonia or tuberculosis. Temperature is assessed with the palm of a hand on the patient’s forehead and anaemia is checked for solely by looking at the colour of the patient’s hands or conjunctiva of the eyes.Concerning treatment, the British National Formulary, the book of all licensed medicines in the UK, contains over 700 pages of small typed print of medications, the majority of which a hospital doctor in the UK can prescribe free of charge with little consideration of availability. In Segbwema there was a price list of drugs covering two sides of A4 to select from, often far less depending on what was currently in stock in the hospital pharmacy and the amount of money which the patient had brought with them. The interface between money and health is something which often does not sit comfortably with those in the medical profession. The questions of who, when, and how health infrastructure and treatment is paid for, dominates health systems all over the world. Limitations of funding occur in every health system, including the National Health Service in the UK, where headlines complaining at the lack of availability of the latest cancer treatments are common place. However, in Segbwema the relationship between money and health is crude and far more apparent at the bedside, with money often changing hands as the patient was wheeled into theatre for an operation.

In addition to spending time at a Nixon Hospital, I was fortunate enough to visit both a government run hospital in Kenema, a town west of Segbwema and a Fistula Hospital in Freetown run by the charitable organisation Mercy Ships. The differences in the standard of care and facilities available in these institutions, compared to Segbwema ,was substantial. The quality of clinical care delivered at the Aberdeen Fistula centre is not far from being comparable to a first class hospital in Europe, with well equipped operating theatres, a pharmacy and laboratory on site. Awareness of the significant differences in healthcare provision in different geographical locations and by different agencies is important for two purposes. Firstly it illustrates how a snapshot of experience gained in one small hospital in one location does no more offer a representative picture of the whole country, than the attributes of a single person could be used to describe the whole population. It also demonstrates the extent of the inequalities that exist within the same country, irrespective of the massive inequalities that exist between countries and continents. As health systems are developed, it could be argued that the distributive justice and fairness of the system is equally as important as the service the health system delivers.

Unexpected meetings and interactions were one of the most enjoyable aspects of my stay in Sierra Leone. One evening, we had a knock at the door of our house in the hospital compound and were surprised to be greeted by a very well dressed man who we gradually discovered had

been studying for his PhD in Lampeter in Wales and was now running a campaign to be a candidate for the next president of Sierra Leone. One of the themes of his PhD concerning peace in Sierra Leone was that peace is more than the absence of war. In other words it takes a stable economy, social mobility, employment opportunities and social cohesion for a country to be truly peaceful. The parallels to health are evident. The World Health Organisation definition of health includes that it is ‘not merely the absence of disease’. Hospital life often sees the acute tip of the pyramid in the illness and suffering that walks or is carried through its doors, but medicine and healthcare provision cannot be seen in isolation from the wider context of housing, nutrition, education and employment. The integration of the multiple components that shape human life is needed to truly improve health. Although whilst I am writing this, I am putting off the job applications that need to be done for hopefully my first posts as a junior doctor next year, I look forward to being part of a profession that aims to contribute in a small way to enabling health and a profession that will hopefully enable me to return to Sierra Leone.

been studying for his PhD in Lampeter in Wales and was now running a campaign to be a candidate for the next president of Sierra Leone. One of the themes of his PhD concerning peace in Sierra Leone was that peace is more than the absence of war. In other words it takes a stable economy, social mobility, employment opportunities and social cohesion for a country to be truly peaceful. The parallels to health are evident. The World Health Organisation definition of health includes that it is ‘not merely the absence of disease’. Hospital life often sees the acute tip of the pyramid in the illness and suffering that walks or is carried through its doors, but medicine and healthcare provision cannot be seen in isolation from the wider context of housing, nutrition, education and employment. The integration of the multiple components that shape human life is needed to truly improve health. Although whilst I am writing this, I am putting off the job applications that need to be done for hopefully my first posts as a junior doctor next year, I look forward to being part of a profession that aims to contribute in a small way to enabling health and a profession that will hopefully enable me to return to Sierra Leone.Robert Burnie, Cardiff, Oct 2010