We met Baindu, a friend and the granddaughter ‘Mama’ Bintu, outside of Connaught Hospital, which, as it was a Sunday, was unusually quiet as we accompanied her to Ward 9. The number of people in the ward indicated that the visiting hours posted on the gate were not being enforced, as there were numerous friends and family of patients surrounding the ten beds. Nevertheless the atmosphere was one of calm and quiet, a sharp contrast to the wards of hospitals we have seen elsewhere in Africa and particularly Maputo Central Hospital. It was a fitting environment for an extremely weak Mama Bintu, who was suffering the effects of advanced cancer of the womb.

A subsequent visit three days later coincided with the second day of industrial action by doctors and nurses, resulting in patients being assisted to the hospital exit in response to the advice to return home as no treatment was available for them. In Ward 9 the family of Mama Bintu were preparing her few personal items and making arrangements to charter a taxi for the five hour journey home. She died two days later.

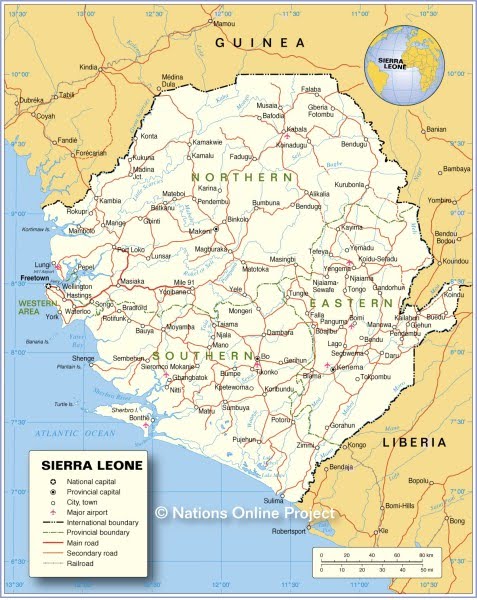

As the strike action of doctors and nurses in Freetown reaches its second week it has just been announced that the talks, involving the President, Ernest Bai Karoma, to resolve the conflict collapsed on 24. March. The health workers union, which represents doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians, is insisting on a dramatic improvement in the pay and conditions, which the Government acknowledges are inadequate but are unable to increase them to the value demanded. At present Doctors receive approximately US$ 150 and nurses US$40 with no additional transport or housing benefits. The increases being demanded are more than four times those figures.

The military, police, other doctors and nurses in training had taken over responsibility of running the two major referral hospitals, the Cottage and Connaught Hospital by providing basic services but the likelihood of this continuing has been put in doubt by the collapse of talks.

The relationship between the Free Healthcare Initiative and the strike action is not immediately obvious and both local media and the BBC world service have so far avoided reporting what is common knowledge in “health care economics”. The wholly inadequate national salary structure for nurses and doctors, results in a common practice of informal charges to patients for a wide range of services, including laboratory tests, injections and prescriptions etc. However when the free services are introduced, patients and the public will expect that such charges will no longer apply, resulting in the loss of the “hidden income” of health care workers. In addition to this, it is envisaged that the free health care initiative will lead to an increase in the number of patients seeking treatment. For a doctor who sees 40 or 50 patients per day in outpatients, an increased work load is not a very appealing prospect, especially if combined with a loss of income.

Emily Spry, a British doctor working for The Welbodi Partnership in Freetown, has expressed her personal and professional difficulties with the strike, on the British Medical Journal’s blogsite.

“The gut reaction was for us to step into the breach at the Hospital. At least to review those who were too sick to be discharged and field the Emergency cases. To be heroes. But there were lots of questions. Safety for one; Voluntary Service Overseas ordered its volunteers to stay away from the Hospitals, as there could be risks in a situation with angry staff and patients... Secondly, and more complicated, the question of whether we should interfere with the healthcare workers’ decision to shut the Hospital down. Who were we to go against their decision? The healthcare workers know the implications of what they are doing; patients will die. But they feel strongly enough that the upcoming abolition of user fees (the President’s Free Healthcare Initiative), cannot and will not work if their conditions of service are not improved to fill the gap left by user fees. They feel that this is their only chance to force the Government to meet their demands.”

“This also leads on to what our role should be here. The Welbodi Partnership’s approach is to form a long-term relationship with the Hospital that will bring slow but, hopefully, sustainable improvement. Breaking a strike is a strategy that could seriously damage important relationships and raise questions about our role.”

At the Theological College, our Salonean colleagues have, with no exception, been supportive of the doctors and nurses, claiming that the national attitude towards employment law and welfare responsibilities is appalling and that the role of the government in addressing the injustice is clear.

A further meeting, involving the President Karoma and the union’s leader Dr. Freddie Coker, was held on Saturday 25th March but failed in its attempt to move beyond the impasse. The immediate response of the Government was to declare that as the industrial action was invoked without providing 21 days notice, it is illegal and all those not returning to work on Monday 28th March will be dismissed and lose all employment benefits.

Today sees the launch of “CARMAASIL”, a campaign to improve the nation’s maternal and infant mortality rates, which are one of the world’s highest and have led Amnesty International to accuse the government of an abuse of human rights. The World Health Organisation indicates that in Salone, there is no more than one doctor to every 100,000 citizens. If this is accurate then there but 60 doctors serving the whole of the nation of 5.5 million.

In conclusion, Emily Spry added “There is no doubt that sick children will die because of this strike. But I am not here to break the strike of the Sierra Leonean doctors and nurses whose duty it is to care for those children. I believe that I am here to try to help them build a system whereby all children have a better chance at life-saving healthcare. And paying doctors and nurses properly is a must for that to happen.”

STOP Press 12.00h 28 March 2010

The BBC Africa Service has just announced that health workers in Sierra Leone say they will end their 10-day strike, after the president agreed in a late-night deal to increase their pay six-fold.