Recently, former mission partner Ken Todd initiated a visit to see Mary Musa, a stately figure who would, had it not been for ill health, been the current Vice President of the Methodist Church in Sierra Leone (MCSL). In an animated conversation, which included stories which took place nearly 40 years ago, she spoke of her family and referred to several of her grandchildren now living in the United States, courtesy of the ‘DV’ system. The ‘DV’ meant nothing to us until a week later, when a friend spoke of her hopes that the ‘DV’, would provide a passage out of Salone

into a future of promise and opportunity. It emerged that a ‘cousin’ within her family had won the ‘DV’ lottery and was entitled to take his spouse with him and so she was intending to become that person, which would, of course, entail marrying him. The Diversity Visa system of the United States government, offers approximately 50, 000 people per annum, from around the world, that same opportunity. It would appear that of the few Saloneans who succeed in the DV lottery, it is extremely rare for them to arrive in the USA unmarried. In Salonean society, the ‘DV’ offers security for more than just the lucky individual, so that marriage and potential procreation become the means of ensuring wellbeing and prosperity for each of the families involved.

into a future of promise and opportunity. It emerged that a ‘cousin’ within her family had won the ‘DV’ lottery and was entitled to take his spouse with him and so she was intending to become that person, which would, of course, entail marrying him. The Diversity Visa system of the United States government, offers approximately 50, 000 people per annum, from around the world, that same opportunity. It would appear that of the few Saloneans who succeed in the DV lottery, it is extremely rare for them to arrive in the USA unmarried. In Salonean society, the ‘DV’ offers security for more than just the lucky individual, so that marriage and potential procreation become the means of ensuring wellbeing and prosperity for each of the families involved.Just over 2OO years ago John Lemon, a Bengali hairdresser, won a similar lottery, but in

reverse. At the time he was the headman of the ‘Black Poor’ in London, whose occupational experiences had included assisting slave trading in Freetown. A decade later, in 1808, he was back in Freetown having ‘won’ a place on the Vernon, where he married Elizabeth, who was, as one historian described “one of the original prostitute wives”, of which there were many. Together, Mr and Mrs Lemon joined the other 2,000 inhabitants of Freetown and Elizabeth became a shopkeeper who, following John’s death would have had little difficulty in re-marrying as men vastly outnumbered women in the ever increasing colony.

reverse. At the time he was the headman of the ‘Black Poor’ in London, whose occupational experiences had included assisting slave trading in Freetown. A decade later, in 1808, he was back in Freetown having ‘won’ a place on the Vernon, where he married Elizabeth, who was, as one historian described “one of the original prostitute wives”, of which there were many. Together, Mr and Mrs Lemon joined the other 2,000 inhabitants of Freetown and Elizabeth became a shopkeeper who, following John’s death would have had little difficulty in re-marrying as men vastly outnumbered women in the ever increasing colony. Today in Sierra Leone, three forms of marriage are accepted by the State: customary marriage, which is often polygamous; civil marriage; and also religious marriage, which if conducted within the Islamic faith may also be polygamous. With the Christian Church being a minority faith, (the United States’ CIA’s statistics claims it to be only 10% of the population), it is not surprising that monogamous marriage is a matter of some concern for those who are committed to growth in church membership. Many of the prospective members of the Church are either Muslims or practice African traditional religion. With the exception of some African Initiated Churches, Christian churches are doctrinally committed to monogamous marriage.

Today in Sierra Leone, three forms of marriage are accepted by the State: customary marriage, which is often polygamous; civil marriage; and also religious marriage, which if conducted within the Islamic faith may also be polygamous. With the Christian Church being a minority faith, (the United States’ CIA’s statistics claims it to be only 10% of the population), it is not surprising that monogamous marriage is a matter of some concern for those who are committed to growth in church membership. Many of the prospective members of the Church are either Muslims or practice African traditional religion. With the exception of some African Initiated Churches, Christian churches are doctrinally committed to monogamous marriage.In many African societies, the nature of marriage, be it monogamous or polygamous, is not the primary concern of the human relationship between a man and a woman, as it is the birth of children which constitutes the purpose of marriage. The Catholic theologian, Benejet Bujo, argues that no issue in African ethics has been more disputed (at such length and often vehemently) than that of the morality of marriage, especially in relation to polygamy. As a Ugandan celibate priest, he writes on ‘the problem of monogamy’, and its challenge to the African church’s authenticity. However, mindful also of the process of rapid urbanisation across the continent, he asks if polygamy “is compatible in modern Africa with the dignity of women”.

Another Catholic theologian, Laurent Mpongo, of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, raises a question that is pertinent in West Africa too, involving the relationship between customary marriage and that of the church. The MCSL requires its ministers who have been married by customary or civil marriage, to have their marriage blessed in church, as “the church’s way of ensuring by means of a special form of service, that her members acknowledge the Christian concept of marriage and vow to live by it”. There are some, including Mpongo, who would be very critical of the Church’s inability to acknowledge the strength of authentic African culture in customary marriage.

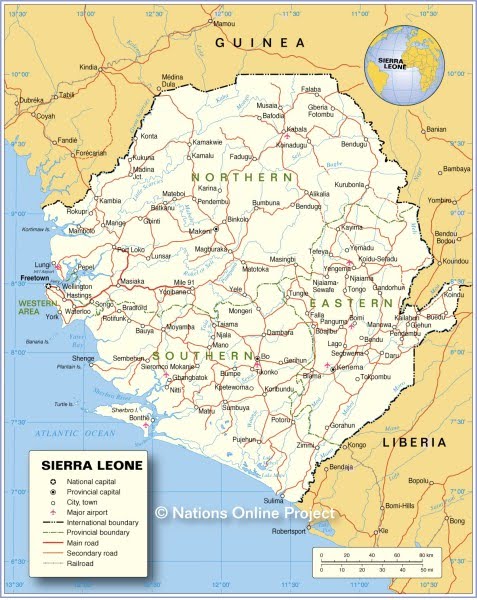

Despite the work of those mentioned above, there appears to be no serious theological reflection on the role of marriage in society generally and its place in the church specifically, in West Africa and especially in Salone. It could be easily argued that people in a fragile country are all too aware of their own socio-political vulnerability to address questions on marriage, especially where religious affiliation is a feature of the tension between polygamy and monogamy. This tension is exemplified in the Western Area of the country, which includes Freetown. It is here where Krios form the largest ethnic group and are monogamous. This contrasts significantly with the Provinces, where other ethnic groups are in the majority. Such a demographic detail is not to be ignored when addressing the theological development of African Christianity in Sierra Leone. It may also be a good enough reason to look elsewhere on the continent of Africa for a debate on an integrated Christian spirituality, where people live their way to a new understanding of marital relationships within the church.

However, the pastoral implications of ignoring the question of what kinds of marriage are appropriate within the membership of the Salonean church, may lead to an attitude of secrecy and complicity as opposed to transparency and integrity. It is the task of church leaders to reflect on which of these would be for better, or worse.

No comments:

Post a Comment